Ain't no one old enough to remember

sonnet no. cx

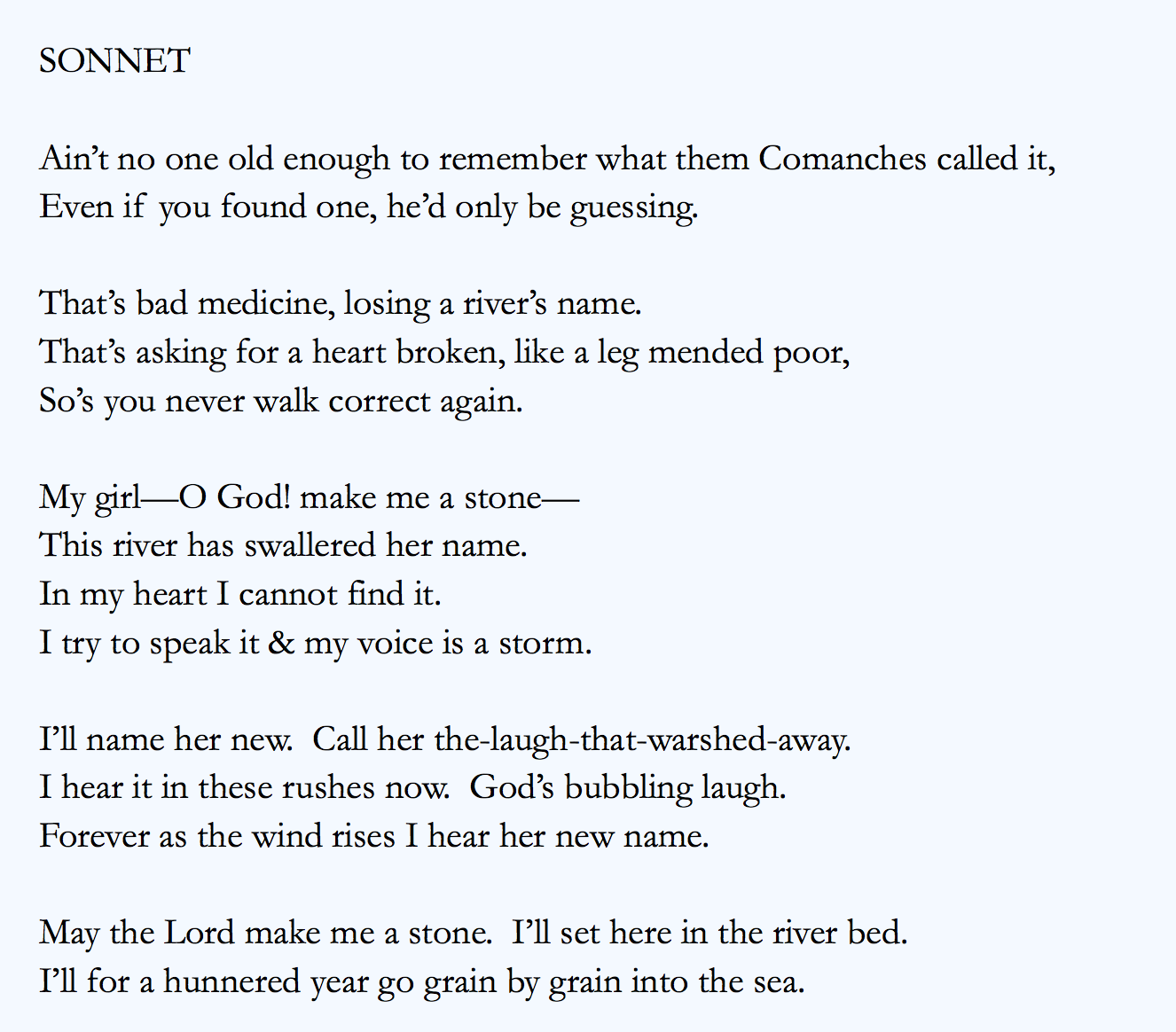

For those reading on a mobile phone, please note that you can tap on the poem to bring a larger version of the picture of the poem. I take screenshots of my poems because I do not like the margins imposed by mobile devices on the lines.

This poem’s format of prose before and after the sonnet comes from my readings of Yannis Ritsos’ longer poems, and I thought I’d see what a narrative frame of the poem does for the poem itself. In a way it relieves the sonnet of exposition, something that I should have taken more advantage of in this poem.

Two men sit in a small craft, drifting quietly with the current of the Guadalupe river. The air is thick again. The motor hums idle in the quiet, one man pilots it to the edge of rushes, fallen trees, they set anchor from time to time and push away the rushes with their hands, climb the riverbank and look over the shoreline. As noon approaches they get hungry, and stop in the shade of an oak, kill the motor and eat fried chicken cold, dipping the torn meat in ranch. Sudden crack of a thunderhead, and the storm’s breeze sweeps in from the hills, chilling the sweat on their bodies. One man splashes into the water, knee deep, and dips his hand in the Guadalupe, returns it to his face, and speaks this song.

The small craft is fitted out with fishing equipment, coolers and water toys. It can regularly burp out the longitude and latitude of the travelers, and came fitted with a ham radio that occasionally sings out from others in the search party. Carelessly, another small craft comes riding down the river. It carries young men and women who laugh at the speed the boat, and the way its pilot swings it side to side. They wave to the men at the shore who instinctively wave back. Their motor is heard even after the boat is long gone from view.